Guest Post by J C Sherrill III

How heat moves, Insulation, Radiant and Vapor Barriers

In relation to Indoor air quality part II

Everyone may be an expert and know a little something when it comes to insulation. We have all heard the saying “It’s so easy a monkey can do it.”

Information can be right or wrong. When you grasp the knowledge of how heat moves, how insulation, radiant and vapor barriers work and have it in your head you will have the ability to think through the job and DIY, You will have the confidence to get it right the first time. With insulation you do not have an easy option to “Fix it” after the wall covering is up.

How Heat moves; The 3 ways:

Radiant: Is like sitting the sun

Radiant barriers act like a reflective shade. It can stop the flow in both directions but this is not the only way heat moves. Radiation can also flow out of your body towards a colder area. Sit by a cold window at night without a lot of clothing in the winter and you can feel this effect.

Conduction: Heat the end of a metal pipe and hold the other end.

Convection: Warm air

Heat moves to cold and the greater the temperature difference the faster the change

Let’s say I go to Dunkin Donuts to get you a cup of coffee. You like it hot, but also want cream. Do I add the cream now or later?

Think about this: The greater the temperature, difference the faster the change. Keep reading and thinking. The answer will be at the end.

Insulation and Vapor Barriers A perspective from a heating contractor.

My information and opinions are based on experience in the field, an understanding of the properties of air and newer building science. Another reference outside of my 2 cents where I have gained a lot of knowledge on good building science is www.advancedenergy.org take a look at what these ”Experts” have to say on proper building science.

Go to buildings scroll down to the Knowledge Library and look at what they offer for free. This is a wealth of quality energy saving “get it right the first time” building science information at their site.

When I discuss walls within this text, my meaning is the envelope of the home that include the Walls, floors and ceilingsVapor barriers VB are in place to prevent moisture from migrating in the wall. Think of rain, it comes from the air. Air can carry a lot of moisture. Think of a Cold glass of iced tea in the summer. Ever seen moisture forming outside the glass? Cold surface + warm humid air. The dew point gets reached; the moisture in the air condenses on the glass

and rains down the outside of the glass. This is a not good thing when this vapor condenses inside of a wall.

Moisture in the air is measured in Relative Humidity. RH is measured as a % present at a given temperature. Warm air can hold more moisture than cooler air. Imagine air as being like a sponge. Now dip it deep in a tub of water, it is saturated. This is like warm air. The sponge can hold a lot of moisture. Now lower the temperature (squeeze the

sponge) the air cannot hold as much moisture at a cooler temperature. RH is the % of saturation the air can hold compared to a given temperature. Cooler air is denser. Air molecules are heavier than moisture molecules

since they pack tighter together. Dew point is the temperature where the air is fully saturated. It is also where condensation will start to form.

Ever witnessed dew on grass? The air was warm and full of moisture during the day. It got cooler overnight, dropped below the dew point and the moisture condensed from the air. You do not want this to ever happen inside of a wall.

Houses do not need to breathe. People need to breathe / Run a fan or open a window for ventilation.

Loose house = more infiltration = more moisture due to vapor migration.

Don’t beat me up on this one. A vapor barrier should never be plastic. A plastic VB will trap water in a wall. If you have a “Bulk water leak” from a roof, window, door trim, flashing failure, pipe leak, etc. Even an air leak from Infiltration can cause moisture to become trapped inside your wall. When this happens your wall is in trouble. This can affect your homes indoor air quality. If you have made this mistake and have plastic as a VB try and keep the inside and outside of the wall bulk water free. By using proper flashing, door and window caulking and fix

any spills or plumbing leaks ASAP.

Keep your home and wood dry and you will never need to be worried about mold, mildew and wood rot.

I have witnessed sagging bags of water, hanging under a house where the home owner installed insulation on the underside of his floor and then stapled 6 mil plastic on the bottom of the floor joist. These water filled tubes on 16 inch centers, made a nasty, moldy, soggy mess of the floor system. He is a commercial insulation contractor and got it

wrong. With a little knowledge, you can DIY with confidence.

A VB should go to the warm side. Usually towards the inside unless you live somewhere like South Florida, etc. Heat moves to cold you are trying to block the air/ vapor movement at the source.

I look at insulation and the VB like having holes in the bottom of a boat. If you have 4 holes and only patch 3 you still have a leak. Keep the insulation and VB continuous. Do not leave voids in the wall around electrical boxes, wires or pipes. Keep the insulation its full thickness and firmly pressed against the floor wall or ceiling. If you use faced fiberglass staple the flap to the outer edge, face of the stud. I have seen pros staple the flap to the inside of the stud wall leaving an air void at the edge of every stud.

You should only have one VB. Two can allow water to become trapped in-between a wall.

Tar paper VS house wrap. I have seen house wrap dissolve inside a damp wall. You cannot use house wrap on a roof so I prefer tar paper. When installed on the exterior of a wall, from the bottom up, any moisture inside a wall can escape through the overlapping layers of the tar paper. Tar paper will protect your wall and will last.

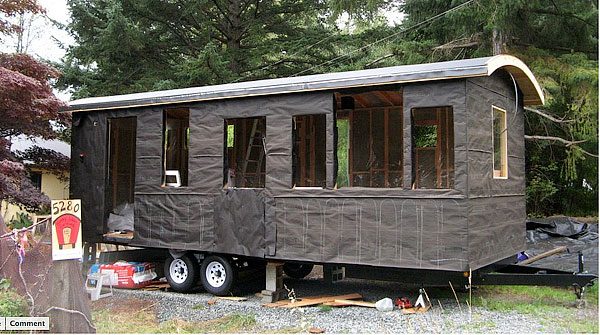

Insulate or not? It is way too hard to do after the inside walls are installed. It is a cheap bang for the buck. It will also make your tiny home much cooler, warmer and quieter.

Insulation Pro VS. Cons of the most common Insulation found in the box stores

Fiberglass, Spray foam, Sheet foam, Cellulose:

Insulation is measure in R values. R = resistance to heat flow. This R value is only half of the story. Some insulation performs better than other per given thickness and cost. The other half is infiltration. Infiltration = air leaks = moisture migration. Before installing the insulation seal all penetrations around piping and wiring in the walls with a good grade of caulk.

Fiberglass: Pros low initial cost easy to install as a DIY job Cons: Furnace filters are made of

the same material. Air can flow right through. *

Spray Foam: Although not usually found in a box store Spray Foam is a great insulator. DIY Kits are available www.tigerfoam.com or you could hire a professional. Foams are resistant to moisture and are a very good vapor and air barriers. Spray foam adds strength to the structure since it acts like a glue. Con: Expensive cost and expensive shipping cost. * Do not install spray foam without a respirator, face, skin and eye protection.

Foam sheets: Easy to install resistant to moisture good vapor and air barrier good insulator. Foam sheets that are cut to fit are a good option. When all your foam sheeting is installed, use Foam in a can, to fill any cracks and voids. *

Cellulose: Made from recycled newspapers is a good low cost insulator. This product has the ability to hold and release some moisture inside a wall. This protects the wall and it has the ability to pack so dense it acts as a VB. I have used this in an attic. Pros have a mesh fabric that they staple up to hold it in place while they blow it in. They can

also install it wet in walls. When it dries it is like dense like paper Mache.*

*Mask skin and eye protection required.

It is critical that the insulation and vapor barrier be installed properly. It is such a menial task that when installed professionally it is usually such a get it done in a hurry job that voids and gaps are present. Properly installed insulation and vapor barriers pays you back over the life of your home in energy savings and prevents moisture from condensing inside of the wall.

You should chase the cost of insulating your home with which type insulation gives you the best R value bang for your dollar. Cost and type may vary from one area to another so you will need to do your homework. Installed properly any type of insulation will perform well in your tiny home.

Radiant barriers:

First to be effective it shouldn’t touch a surface so it needs an air space to prevent conduction. Dead air space is an insulator but doesn’t have as great an R value as insulation for the same thickness. Should you have much infiltration inside of a wall it would render the air space useless as an insulator. Second a small layer of dust will render a Radiant barrier less effective. Roof color light or dark? A white roof is best for hot climates. Metal roofing with a light color will provide your home a Radiant barrier.

I found this from NC Advanced Energy: New construction radiant foil on bottom of plywood roofing testing: “Radiant Barrier roof sheathing appears to reduce summer/cooling loads by about 3 Percent of summer/cooling loads” For the added cost I am not sold on foil radiant barriers.

Insulation properly installed can help keep your home more comfortable, use less energy, make it last longer, quieter and improve the indoor air quality. Stay safe.

Question: Let’s say I go to Dunkin Donuts to get you a cup of coffee. You like it hot, but also want cream. Do I add the cream now or later? Answer: I would add the cream at Dunkin Donuts.

Visual example: Empty a cup of ice in your yard in the winter, how long does it last? Now do it the summer. The greater the temperature, difference the faster the change.

© 2011 J C Sherrill III Reproduction without permission prohibited.

I appreciate the information. What is your opinion on less toxic insulation options? Many of the trailer-built tiny homes I’ve seen featured here and on similar blogs are built by people with a desire to avoid many of the more toxic home building products for a variety of reasons. What is your opinion about the effectiveness and safety of using say vegetable based spray foams, or recycled denim insulation?

I do not have any data on the types of insulation you have mentioned. I’d ask for a Material Safety Data Sheet MSDS sheet and do your own homework before you place anything you are concerned with before installing inside your tiny home, would be my recommendation.

This question of which insulation is best for people, for the planet, for your pocketbook is quite complicated.

Other factors not discussed in this article are the carbon footprint of the material used, the embodied energy of the material used, and the impact on the environment, both local (like your indoor air quality) and global.

Fiberglass is hardly ever the best choice. It requires a lot of energy to produce. It can be installed well when blown in, but batts will never fill the cavity completely. It’s impossible to install batts perfectly. The problem is not with air passing through the fiberglass (furnace filters are super thin, come on!), it’s convective loops forming in the air gaps between the fiberglass batt and the framing/sheathing.

Spray foams work really well. Unfortunately, even the vegetable-based foams are still mostly petrochemicals, and the foaming action when installing them releases nasty chemicals that contribute to global warming. They also have a high embodied energy. Another factor with foams is remodel ability – foams make it really really difficult to run another wire or another piece of plumbing in a wall some day down the road. And yet another reason to not use foam is recyclability – once a piece of framing lumber is covered in foam, it’s likely heading to the landfill instead of being reused when your house finally meets it’s maker.

Cellulose is a recycled product. It has low embodied energy. It has low carbon footprint. It doesn’t leach any toxic gasses into your living space. It needs to be dense-packed. This creates a better air-seal, and prevents the cellulose from settling. Some older builders will tell you not to install cellulose because it settles. It did, before people knew how to dense-pack. It’s no longer an issue with houses that sit on the ground. With your little house on wheels, it might be worth considering that all of the shaking could settle it out a bit, especially if your install wasn’t perfect in it’s density. If I where planning on doing a lot of towing, I would hire someone to spray the cellulose instead of blow. Spraying, as discussed in this article, creates a paper-mache like fill that is stiff and won’t settle.

That’s a great summary of those options; thanks for posting that. I use cellulose whenever I can; once one factors in the impact of manufacturing and eventual waste (not just the efficiency of insulation once it’s in place) cellulose is usually the most sustainable option.

I found this at spray-foam-chicago.com

Spray foam is an airflow retarder. In fact, in a 3 1/2″ sample, open cell foam is 24 times less permeable to air infiltration than a fiberglass batt. And since it also fits better than a fiberglass batt, with the foam actually adhering to the studs in the wall cavity, the combination insures the best possible reduction in air infiltration in the walls of a new home.

“The problem is not with air passing through the fiberglass (furnace filters are super thin, come on!), it’s convective loops forming in the air gaps between the fiberglass batt and the framing/sheathing.”

I would agree with this statement Devan, but for a novice builders reading this, fiberglass insulation is made of the same material. I would also state that should you ever remove any fiberglass insulation and see dirt streaking in the insulation this a clue as to where you have had some air infiltration into the product.

Thanks for the good information.

We first installed Johns Manville formaldehyde-free fiberglass insulation because we wanted to reduce toxicity. When we’ve been back to the hardware stores to buy more, we can’t easily find it but the “Pink Panther” (Corning) fiberglass insulation now comes in a formaldehyde-free version too and it’s really reasonably priced. I would love to go with recycled denim, but it’s just cost prohibitive for us. The formaldehyde-free is a good compromise.

It’s a bit confusing when you jump directly from the topic of vapor barriers to air/weather barriers (tar paper vs. house wrap). Vapor barriers and air/weather barriers are two entirely different things, but the uninitiated might not understand that from the article.

The information I have provided is of my opinion and that of good building science as to how to construct a wall. It is a very a condensed version of what to do.

In my opinion tar paper or house wrap use on the exterior wall is to protect the wall from bulk water / rain or wind driven rain. When layered properly it would allow drainage if ever needed.

The vapor barrier is to prevent moisture from entering the wall from the inside of the wall as vapor.

Plastic VB can trap any bulk water that gets inside a wall and it has no exit out.

Don’t just take my word for anything I have stated. This is to get you folks thinking about the health of you and your home. The uninitiated need to do their own research. Advanced Energy is a good place to start.

I’ve been following this series because our family is moving back into our 31ft rv for winter while we wait to build offgrid on our homesite.

My question would be to insulate or not insulate? I know a lot of people who put things like reflectix or other coating over their windows in the rv….but then you say running the propane/catalytic heaters without ventilation is bad. We have ceiling vents which open but is that enough? We won’t have electric, only a generator.

So do we make the rv as airtight as we can to keep it warmer and to use less energy or do we leave it as is for more ventilation and indoor air quality? I’m confused on this one.

Bad …………………… CO can kill you and your entire family.

I ma not meaning to come across as harsh but look up the symptoms of CO Poisoning, a poisonous odorless gas to determine the parts per million that go with the symptoms and then determine for yourself just how much of a dose you can handle.

Why take the risk?

I can’t tell you how much air to bring in to dilute a poisonous odorless gas you have spewing inside your tiny home.

Get a vented heater approved for use inside a camper. Have it installed properly get a CO alarm and insulate.

Olympian wave is a catalytic heater which is vented to the outside. I’ve talked to many folks who live full time in rvs who have used one for years and feel it is very safe. I can’t afford $1000 for the boat propane heater you and Jay advertise so what would another safe option be to keep the family warm and safe during winter without electricity?

No flame, (flue or chimney) First red flag

Tech Specs

Weight: 16.95 lbs.

Dimensions: 21 1/4″H x 15″W x 4″D

Warranty: Mfr. three year conditional warrranty.

Manufacturer: Camco Mfg Inc

Mfg Part #: 57351

Tech Notes:

AGA and CGA approved.

4200 to 8000 BTUs.

(For use in vented areas only.) Second red flag

Safety Note: Any fuel burning ventless appliance needs adequate air exchange to replenish Oxygen and remove products of combustion. Standards require at least a 1 square inch fresh air opening for every 1000 BTUs of propane used by any appliance. Replacement air (oxygen) is provided best by two vents, one low on an outside wall and the other high on another outside wall. (Third red flag you need 2 holes in 2 walls Cross ventilation)of 8 sq inches total for this heater per the manufacture’s instructions)

Massachusetts Exception: This item is prohibited for sale and delivery into the state of Massachusetts.

THIS WOULD BE A HUGE CLUE FOR ME THIS HEATER IS NOT SAFE TO USE.

I hope you can find a better choice as this is a non vented heater)

Finding heaters that produce small amounts of heat (BTU’s) that are vented are a problem due to not having a lot of choices. You need to look for and read the fine print whit this type of purchase.

http://joel.searchwarp.com/swa421497.htm

For another opinion take a look here.

Stay safe.

Thank you for pulling this information together for us. It is great to have some professional, well-researched advice.

If “A vapor barrier should never be plastic” what should it be then?

(The tar paper/house wrap isn’t the VB; the VB goes on the inside on top of the insulation/behind the drywall if I’m not mistaken…)

It depends on your local climate and code requirements. Insulation facings, foils, or even latex paint can be used as vapor retarders in some areas – but only some. Vapor retarders are a tricky topic with few universally applicable answers.

If you use sheet goods, 4×8 wall materials, like paneling drywall and plywood you have somewhat air sealed the wall. This is why they will let you use a VB paint. You have no cracks for air leakage. You will still need a VB if you use sheet goods.

Tongue and grove boards set up the interior walls to act like a colander or a sieve for air movement without a good vapor barrier behind them.

Water flow is what you are trying to prevent inside of a wall and you try and stop it on both sides from ever entering the wall.

The A B C’s of how Water flows

Air

Bulk

Capillary

The closed cell foams offer a built in vapor barrier since these will not hold water (unlike the sponge type foams / Open cell type)

My first choice would be spray in place foams.

My second choice: Sheet foam. I would weigh the cost of the spray foam VS the materials and time to cut 2 pieces.( I’d want a good thickness for the better R value) and install sheet foam with foam in the can sealing the cracks around the boards. Be sure to figure the cans of foam into your total cost when figuring the meterials.

Cellulose: Made from recycled newspapers is a good low cost insulator. This product has the ability to hold and release some moisture inside a wall. This protects the wall and it has the ability to pack so dense it can also act as a VB This would be my third choice even though I may need a pro to do the ceilings walls as a wet spray.

If I used Cellulose in the walls and ceiling I’d use sheet goods or a Kraft type VB over T & G boards. This would keep it from falling out of the cracks over time.

I would use sheet Foam against the floor.

Although I have used Fiberglass insulation It would be my last choice. I do not like the fact that air can blow right through it.

I’d use a Kraft paper backing. I have both Fiberglass and blown in Cellulose in my attic. I had just a little amount of Fiberglass in the attic (older home). I rented the machine from Lowe’s and added a layer of Cellulose over the existing Fiberglass. This covering packed down so dense it helps seal my attic like a VB. If you don’t blow air through you stop the moisture flow.

It is worth stating again VB’s are in place to stop the air flow which will stop moisture from flowing.

That folks is what a VB is needed for.

Options in insulation and vapor barriers and retarders vary by state and by building codes. I know some states require the vapor retarder to be under the siding only, others under the drywall, and still others none at all. Here in my part of the country, they require a vapor retarder between the insulation and the sheetrock (drywall).

Around here, if you ask for a vapor barrier, you get plastic sheeting and a warning of NOT to use this in the walls, not even in the bathroom, as it will trap moister and cause mold and rot. A vapor retarder here is tar paper, roofing felt, asphalt backed kraft paper.

Even if one is building a tiny home on wheels and feel that building codes do not really apply to them, it is still a good place to start and get information when deciding what should and should not go up on or in the walls in that part of the country.

I just wanted to add another insulation option to the list that folks might want to look at which is stone wool (or rock wool). There’s lots of great info on Roxul’s site at http://www.Roxul.com but basically it’s a rock-based mineral fiber insulation comprised of Basalt rock and Recycled Slag. Basalt is a volcanic rock which is abundant in the earth, and slag is a by-product of the steel and copper industry. The minerals are melted and spun into fibers. It also doesn’t have tons of formaldehyde like most of the fiberglass options.

I have not found this in our area at the home improvement stores. Another good choice.

I’m curious, and this question would probably be more appropriate for the previous post on the subject of ventilation, but it didn’t occur to me – but I’m wondering if someone has come up with an equation or basic rule of thumb regarding ventilation, square footage (or even cubic footage/yards of air in a house), and number of people living there. That might not make a whole lot of sense, I realize, but my thoughts are that if I’m a single guy living in a 2,000 square foot house, I don’t need to be concerned about the amount of moisture I’m putting into the air via respiration or cooking on the stove. If I’m living in 150 square feet, it might be a concern. At what point does moisture become a concern that wouldn’t exist in larger homes?

I don’t have the equation, but from actual experience, when I was living in a 300 square foot cottage there were moisture problems when cooking (no stove vent), so I would need to open windows in the winter. I haven’t noticed these problems in a 400+ square foot apartments that I have lived in.

When you see condensation forming inside your home. Like in the shower area, on walls and or the windows. You have everything needed for mold mildew to thrive. Trust me it is a problem for larger homes in these areas.

15 CFM would be OK. It may just be to much. A bath fan is about 50 CFM and a kitchen hood is around 100 CFM or more. Opening a window a little would be a good option.

You can not smell CO. But if you still smell your last visit to the loo or what you cooked for supper it would be my guess you need to open a few windows a lot…………….

Now how do you get power to operate this fan off grid?

Any ideas?

Powering a fan off-grid is easy. Either use solar panels, wind turbine, or one of those fans that operate directly by wind power.

An appropriately sized solar panel can operate a proper-sized computer fan for ventilation, but stopping in an RV Store should also provide a fan for off-grid use. The fan size, in cubic feet per minute, is determined by what you want to vent. Smaller rooms=smaller fans, in general.

I won’t go into details here about code requirements and formulas for determining fan size/capacity, as that can be found locally, but this should give you some ideas. Think outside the box!

What about those solar powered attic fans used for venting attics? Seems as though that might take care of business. I can’t imagine one of these fans drawing so much load on your Photovoltaic systems either…..?

Solar fans may help remove dampness in the summer.

It would mainly depend on the temperature and humidity of the air outside. An example would be if it were raining outside. During rain storms or around more humid parts of the country the humidity may be much higher outside during different times of the day.

If your home has wheels you could winter over to a warmer climate just by moving. Move back up North during the hot parts of summer.

Does anyone have any real life experience with solar fans controlling humidity inside a tiny home?

If I were to build a new home and have spray foam insulation properly installed, thereby acting as a “very good vapor and air barrier”, would I still use a house wrap vapor barrier, such as Tyvek or similar? I realize the house wrap would protect against bulk water leaks, however, wouldn’t I then be violating the idea of “you should only have one VB”. In other words, would spray foam insulation plus house wrap allow water to become trapped in-between a wall? Thank you very much for clarifying this as I want to make sure I get this part right.

You’re confusing your terms, I’m afraid. House wrap is not a vapor barrier; Tyvek (as one example) is vapor permeable, which ostensibly allows moisture in the wall assembly to dry to the outside. So, with closed-cell spray foam and Tyvek, you’d have a vapor barrier at the interior and air/weather barrier at the exterior – which is what you want, unless you live in a particularly hot or humid environment.

Great answer. You have got this figured out.

When constructed properly a wall can dry from both sides.

With foam on the inside wall it will air seal so tight it will not get wet from interior water vapor.

Thanks You get an A+

What about HRVs (Heat Recovery Ventilator)? They are code here in Canada (Ontario at least). Are there small units that could be used in a tiny home to refresh the air and retain the heat?

I was just thinking of this and was about to post a link when i saw Hazels response, I think that would solve alot of the issues, it can be placed on a timer since they are not made for tiny homes therefore reducing energy usage ?? Any thoughts?

http://www.smarthome.com/3033A/HE100-Air-to-Air-Exchanger/p.aspx

This thing would be rather large for a small home 31 x 19.5 x 14 and it needs some duct work and a drain in cold climates.

You also will need a 110-120 Volt AC GFI electrical outlet. It is over kill in its capacity. They recommend a timer for smaller homes. The smallest home they show is 1500 sq ft home it provides 9.3 air changes per day.

It uses 100 watts of power which in an off grid home may be a problem.

“Houses do not need to breathe.” This “fact” is not categorical. It depends upon the building materials/system. For example, a hygroscopic system like strawbale walls (meaning the material naturally takes on and releases moisture) MUST be breathable. If it’s not, you end up with compost inside your walls. Indeed, there are experts who disagree with the “tight house” theory, feeling that it goes too far. That said, the gist of the article — that you don’t want to trap moisture inside walls — is absolutely correct. The fallacy, if there is one, is the belief that one can make a vapor barrier sufficiently monolithic to keep all moisture out of the wall. All barriers will leak. And when moisture gets inside a wall, it must have an escape route, or there will be trouble.

Rick stated:

“Houses do not need to breathe.” This “fact” is not categorical. It depends upon the building materials/system

Rick you are 100% right.

I live near the coast of NC in a warm humid environment where we use 2 x 4 construction and not straw bale to construct homes. The intent of my post was to get the folks using showers, cooking and breathing inside tiny homes to understand how air moves and how this applies to insulation when building their homes so they may stay safe. I didn’t think about straw bale construction only about homes using 2x framed type construction.

Ok I’ll contradict myself. If you have read thus far a wall can breathe and from both sides of the wall.

When I state that houses do not need to breathe people need to breath I have had folks tell me that they need to build a loose house. This creates problems if you do it loose from the start. Loose is out of your control as far as infiltration goes. You can control ventilation by opening a window or using a fan. A leaky house will get worse when the temperature outside is greater or the wind blows harder due to infiltration.

The real building trick is to have any wall constructed so as to stop water or vapor migration in from entering either side and to prevent vapor from ever condensing moisture inside a wall.

My intent here was to get the readers thinking how good building science works. I would hope they would dig deeper and find out more than my tiny condensed Readers Digest version on this blog.

A good design wall will take into consideration the construction materials and try to stop moisture on both sides but having the ability to release (breathe) moisture back out or in should it get in in the first place.

Moisture will migrate through ½ plywood given enough time.

“Hygroscopic system like straw bale walls (meaning the material naturally takes on and releases moisture” This is what I was trying to state about cellulose insulation and another reason why it works so well.

Rick thanks for a great reply and I do stand corrected. I would like to learn more if you would care to add to this blog on straw bale wall construction.

Has anyone put rammed earth in the walls and floor for heat retention and cooling in summer? I think that would be the best step. Please post any articles on this. Also radiant heating ideas for the floor in tiny houses.

We should always use recycled products to help our environment. ‘

<a href="Newest short article from our blog site

http://www.prettygoddess.com

Thanks to everyone for the thought-provoking article and conversation! Does anybody know how sheep’s wool stacks up as a moisture-controlling insulator? I found the link below, which helped me better understand R-values and U-valuess, and I know wool has moisture-wicking properties….

http://petermueller.typepad.com/pm-on-renewables/2011/12/pros-and-cons-of-sheep-wool-insulation.html